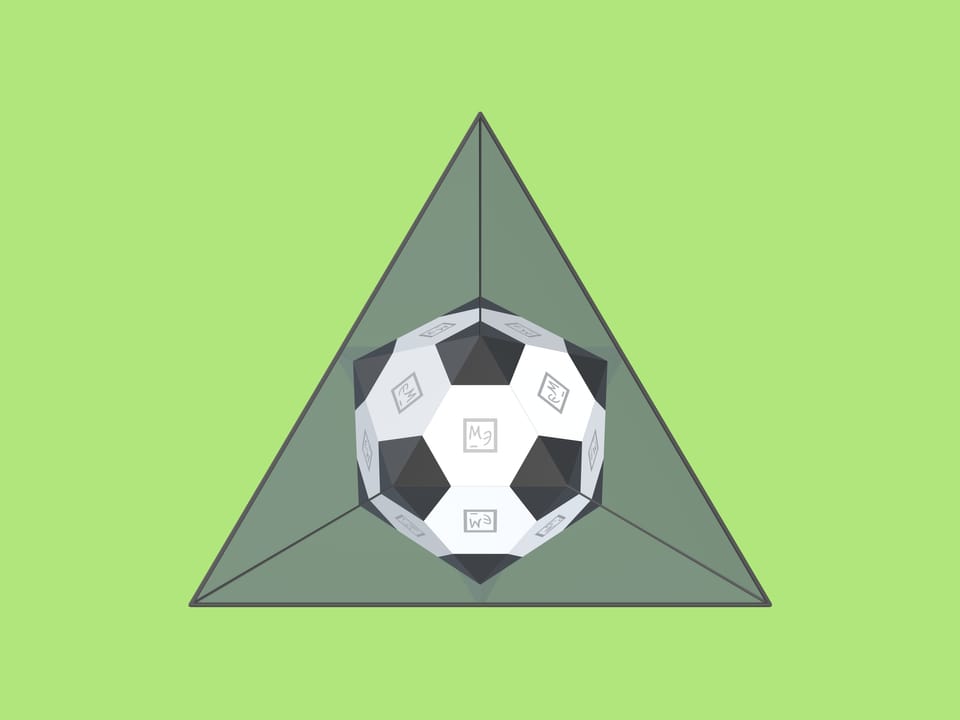

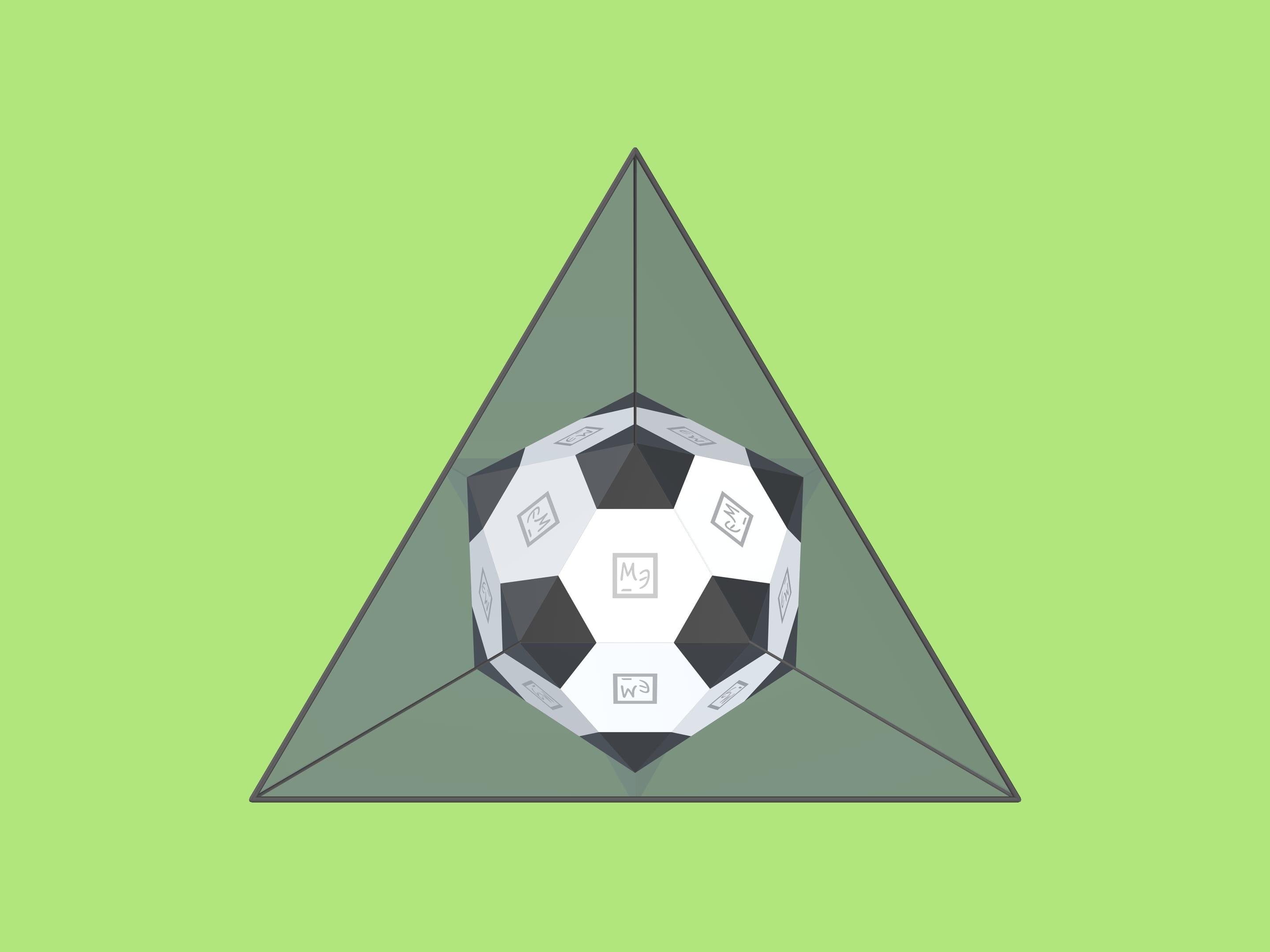

The surface of a classic soccer ball is composed of 12 slightly curved black regular pentagons and 20 white regular hexagons.

By the way, such a ball was not always considered ”classic”: this cut and colouring were first used for the official world cup ball in 1970 in Mexico. The black-and-white colouring was then chosen from сontrast considerations — so the ball was more visible on then common black-and-white TVs. It was even named Telstar — after a TV satellite. In the years to come the official balls changed their colourings, but the cut remained unchanged until the 2002 championship in Germany.

From a mathematical point of view, a classic soccer ball is a truncated icosahedron. This fact and the theory of reflection groups (in three-dimensional case — of Coxeter groups) allows one to make a simple yet beautiful model.

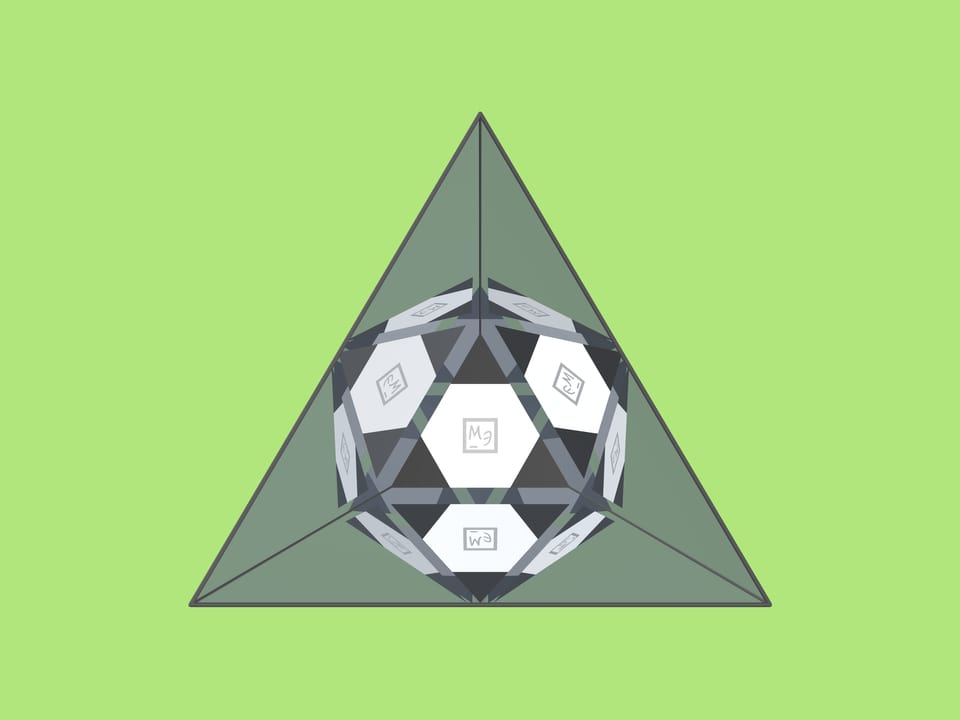

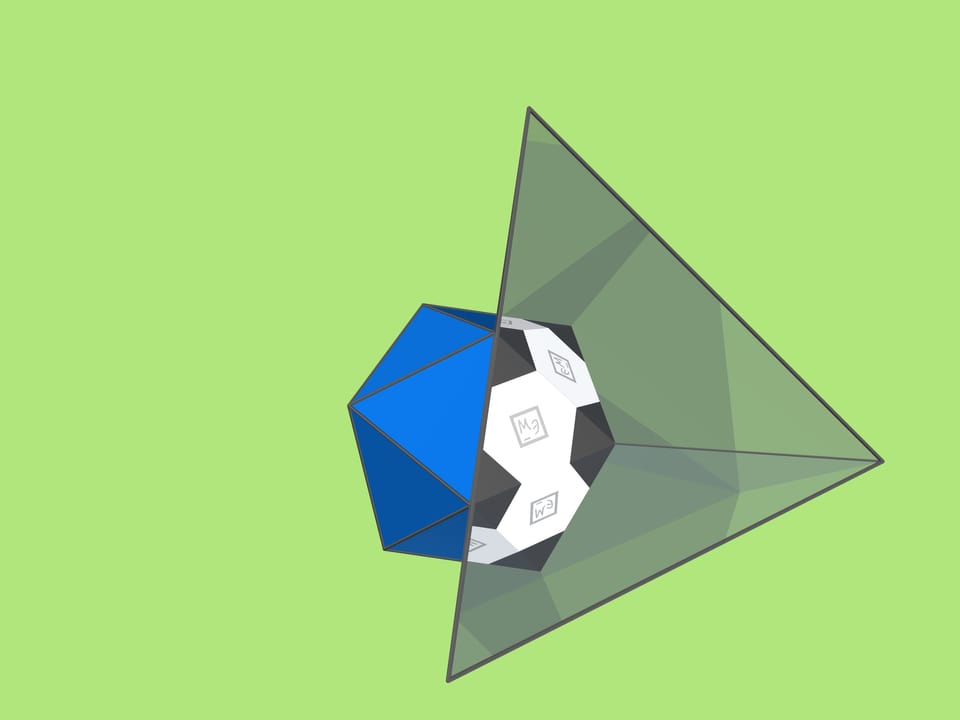

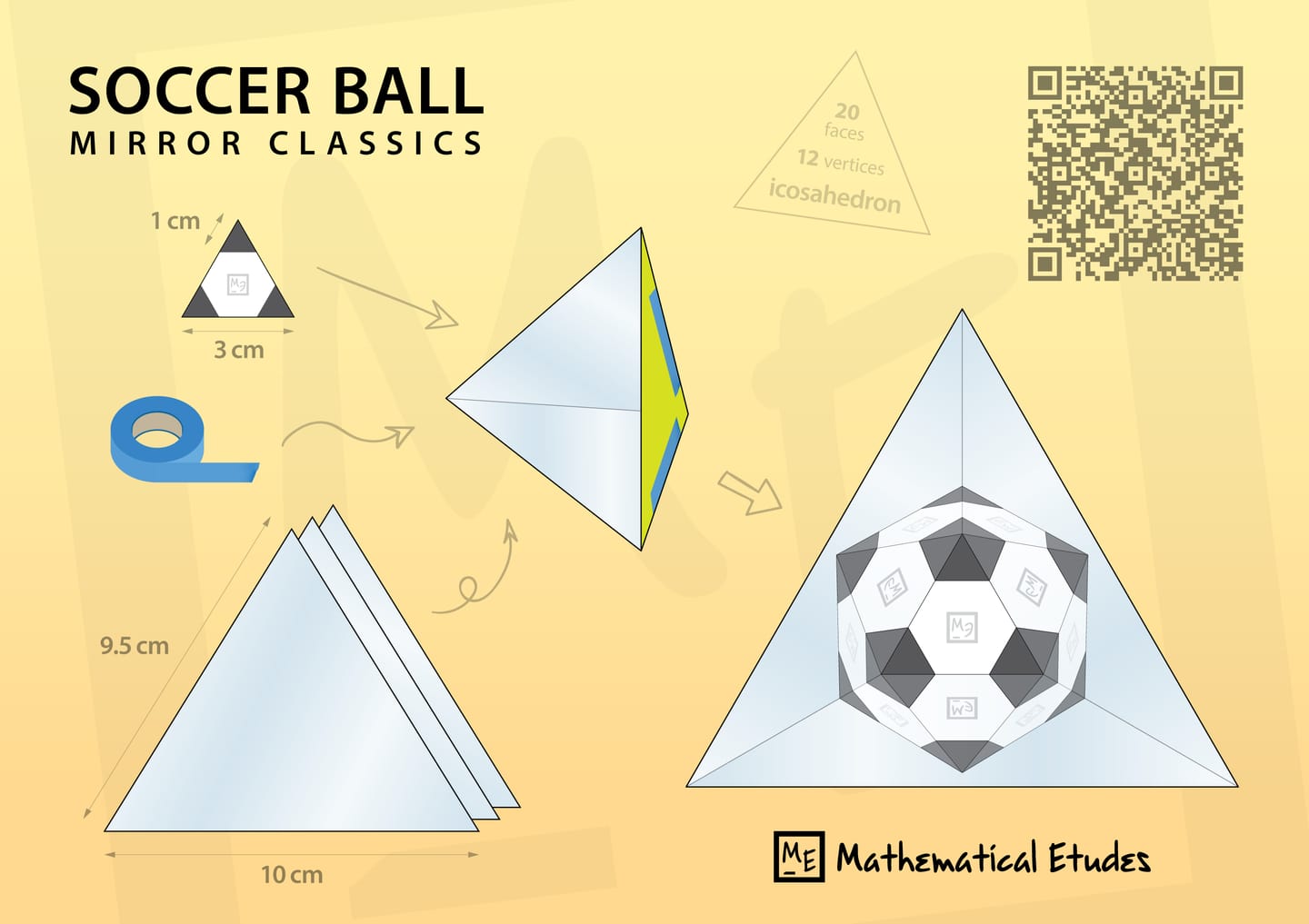

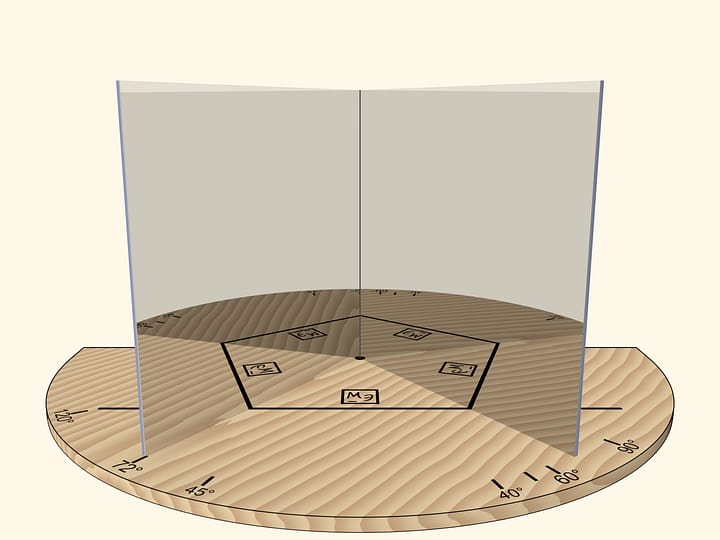

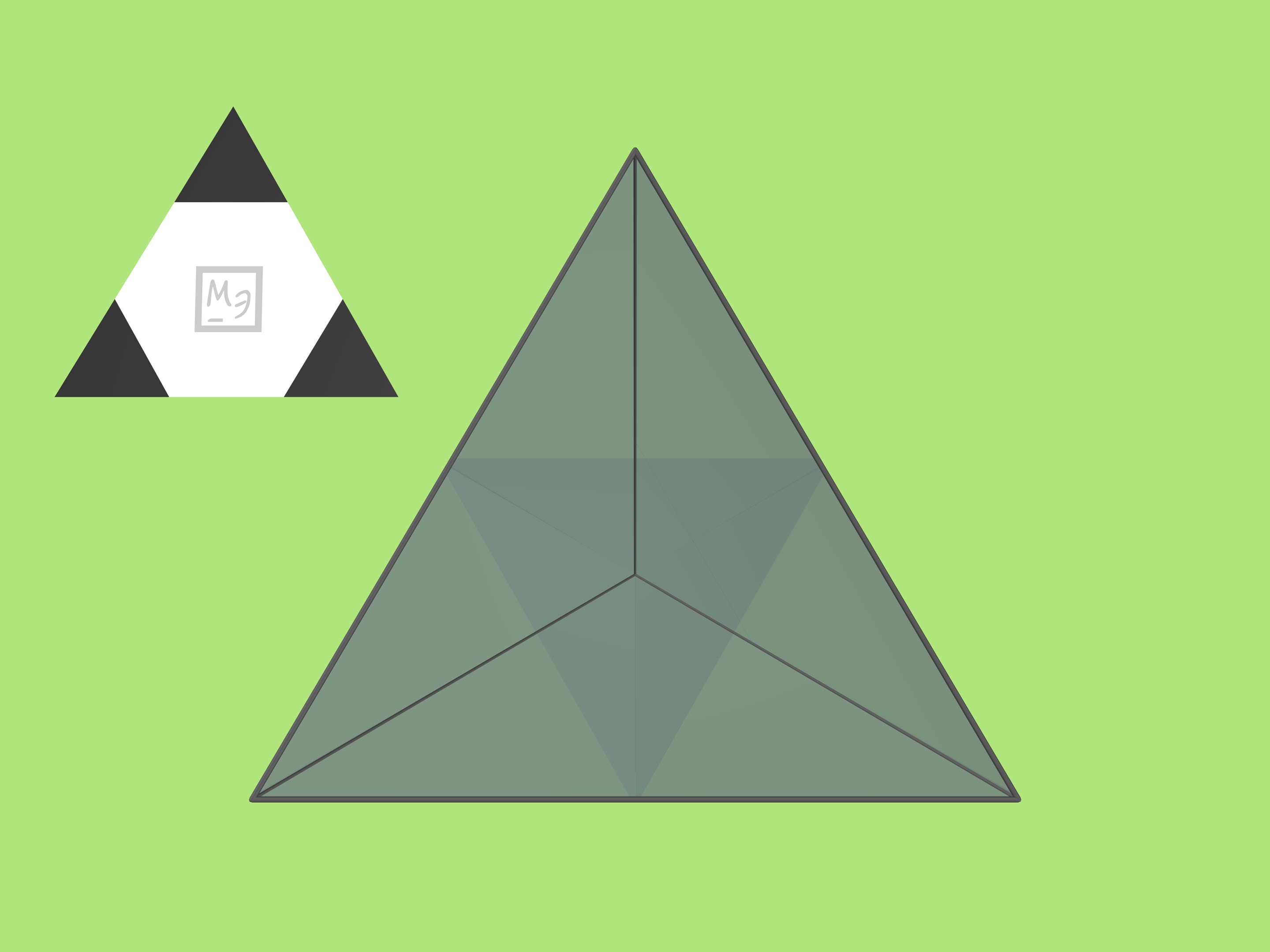

One should take a trihedral angle composed of same isosceles triangles. Given the base length $a$, the length of legs that are glued together to form the trihedral angle should be $r=\frac{1}{4}\sqrt{2(5+\sqrt{5})}\,a$ which with a good precision is $r\approx0{.}95\,a$. (For example, if $a=10$ cm, then $r=9{.}5$ cm.) The mirror angle is very close to that of a regular tetrahedron, but yet differs.

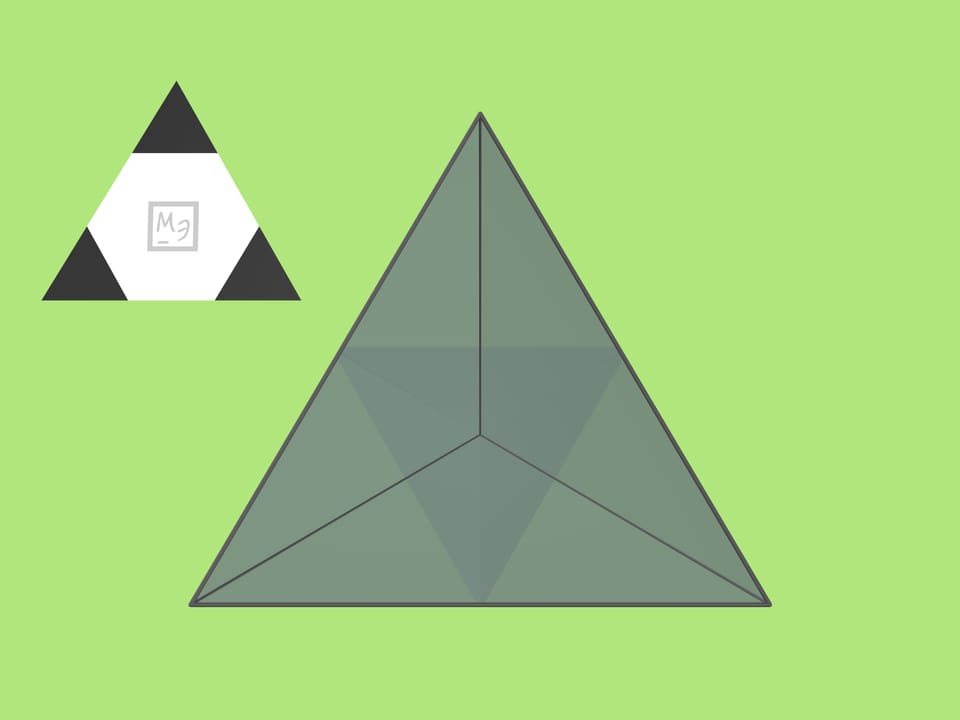

Another important detail is a (plane) regular triangle coloured black-and-white in such a way that the white interior is a regular hexagon. (To achieve this, the sides of black triangles should be taken three times less than the side of original regular triangle.)

If such a triangle is now put in the trihedral angle, a model of a classic soccer ball is seen inside! The image won't change if the angle is moved around the line of sight.

For the ”ball” to be seen completely, the triangle put in shouldn't be too large. One should not put it further than a third of the mirror angle's height from the vertex. (That is, with the base of the mirror triangle being $a=10$ cm, the side of triangle to put in can be taken $3$ cm, so the sides of small black triangles on it — $1$ cm.)

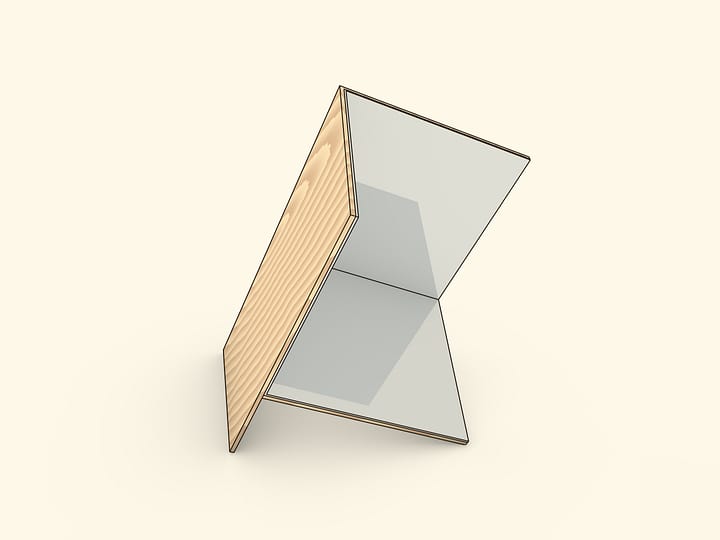

The simplest way to make the isosceles mirror triangles is to cut them out of plastic with mirror coating. They can be put together with duct tape or with wide electrical tape, gluing the legs of triangles — the trihedral angle's edges.

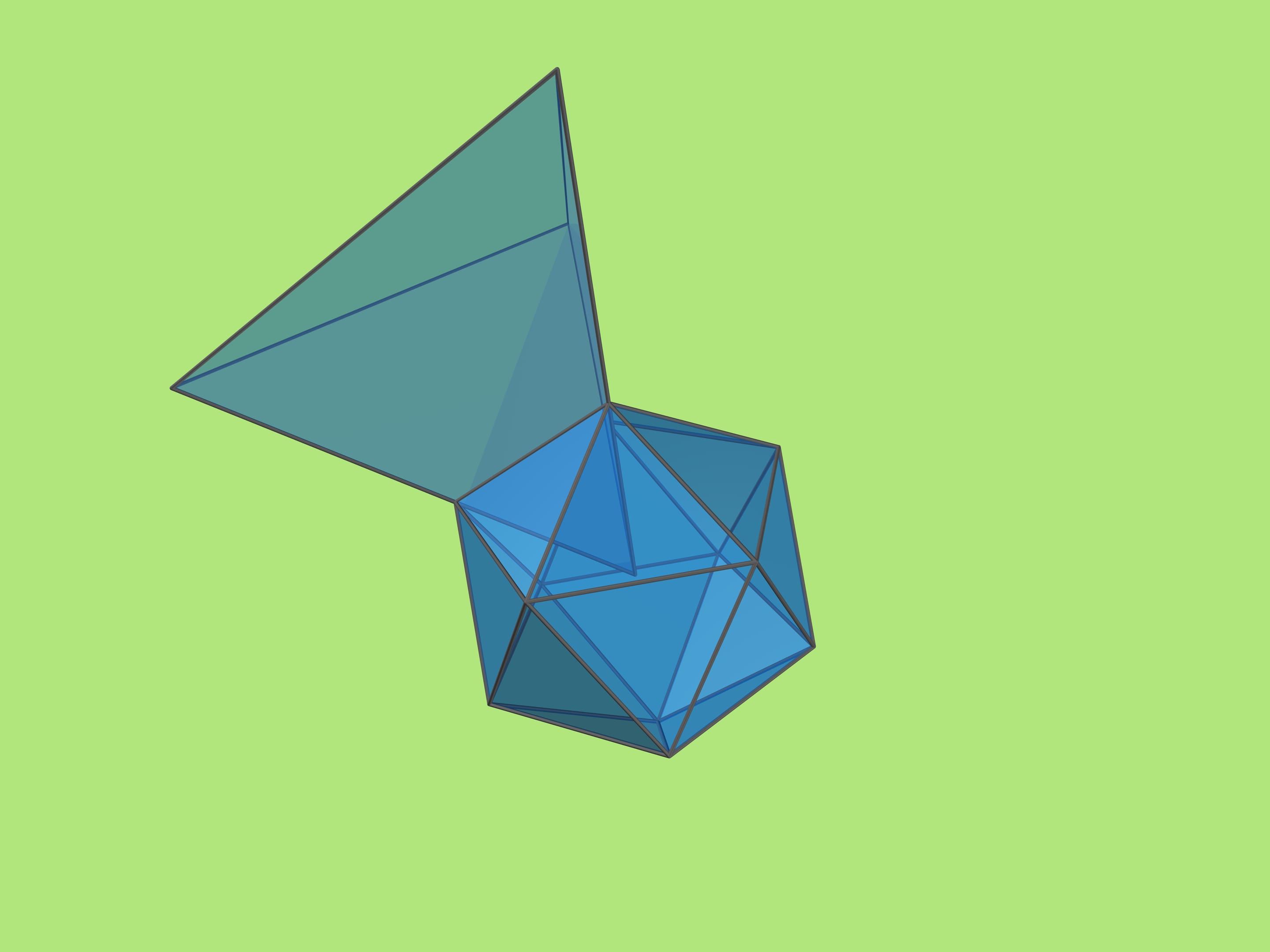

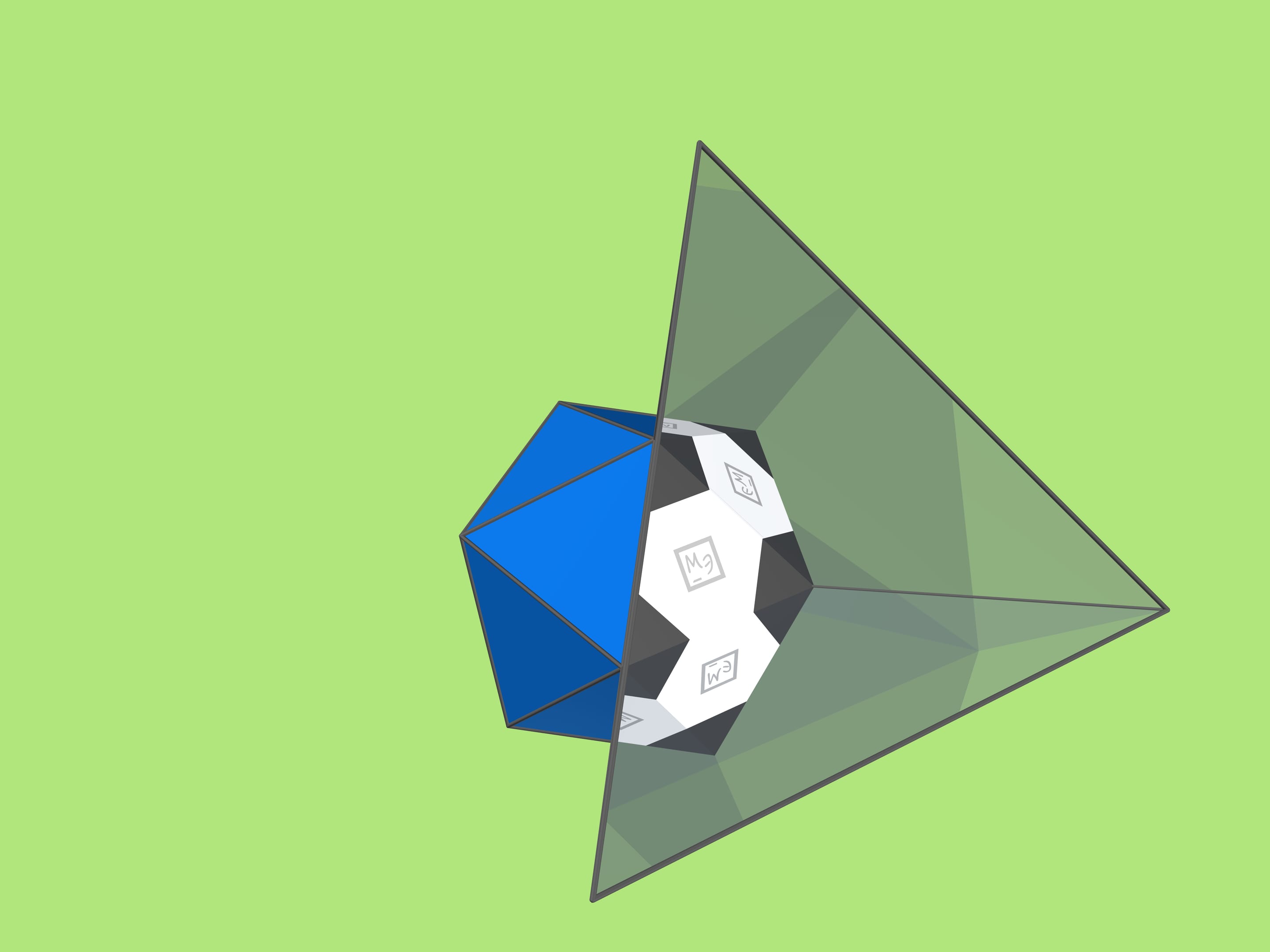

What kind of magic mirror angle is it that the mirror image forms a soccer ball? (In fact — an icosahedron, which is even more clearly visible if one puts in a solid color triangle.)

The mirror angle is associated with the icosahedron itself: its vertex is in the icosahedron's center, and the mirrors cross the sides of one of its edges. That is where the conditions on the sides of isosceles triangles forming the mirror angle come from: if the triangle's base $a$ is the length of icosahedron's edge, then the leg $r$ is the radius of its circumscribed sphere.

And the fact that the image in this mirror triangle is an icosahedron is guaranteed by the theory of reflection groups.