The Pythagorean Theorem (and its inverse) completes book one of Euclid’s “Elements”. Proposition XLVII (47) states: In right triangles the square on the side enclosing the right angle is equal to <taken together> the squares on the sides enclosing the right angle.

The familiar term “hypotenuse” comes (via Latin) from the Greek: “subtending the right angle” is a literal translation of the text of “Elements” — ἡ τὴν ὀρθὴν γωνίαν ὑποτείνουσα.

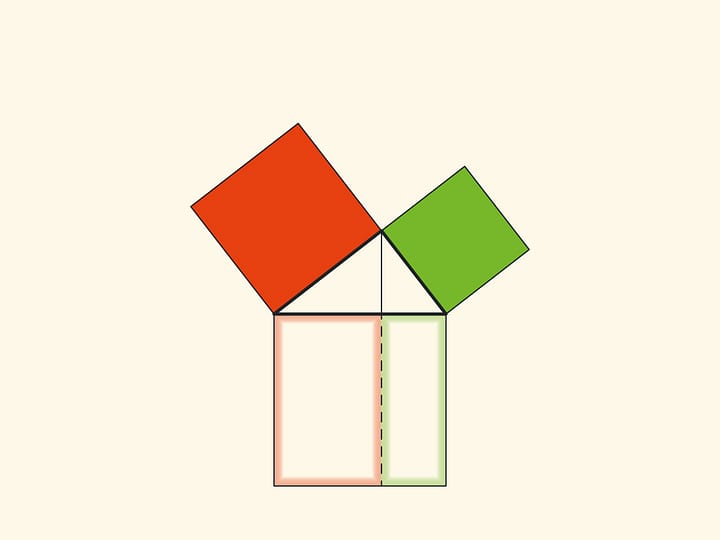

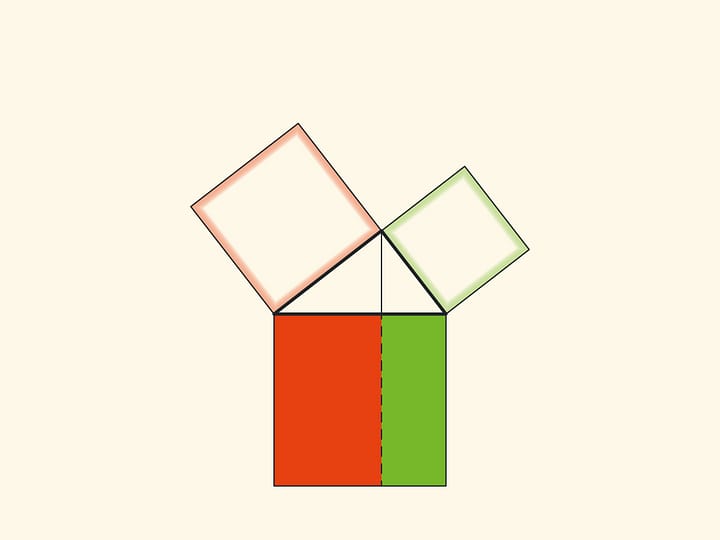

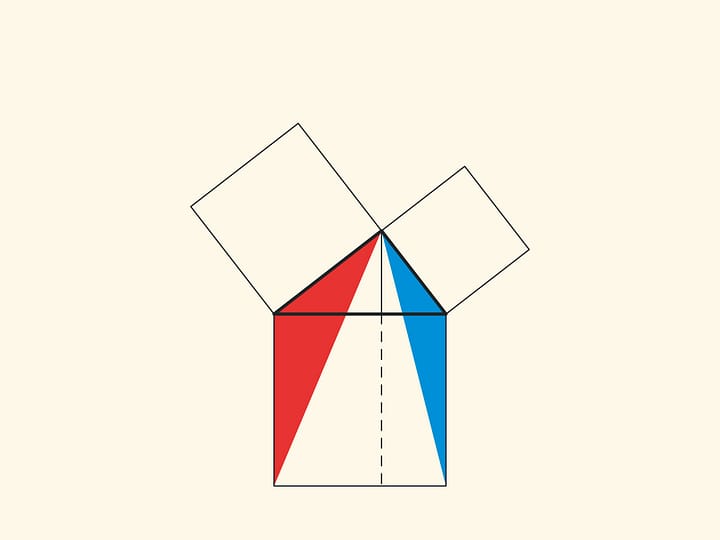

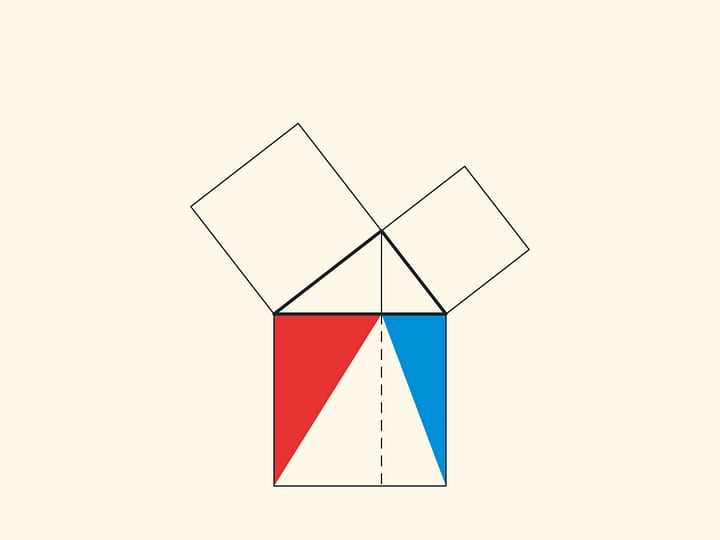

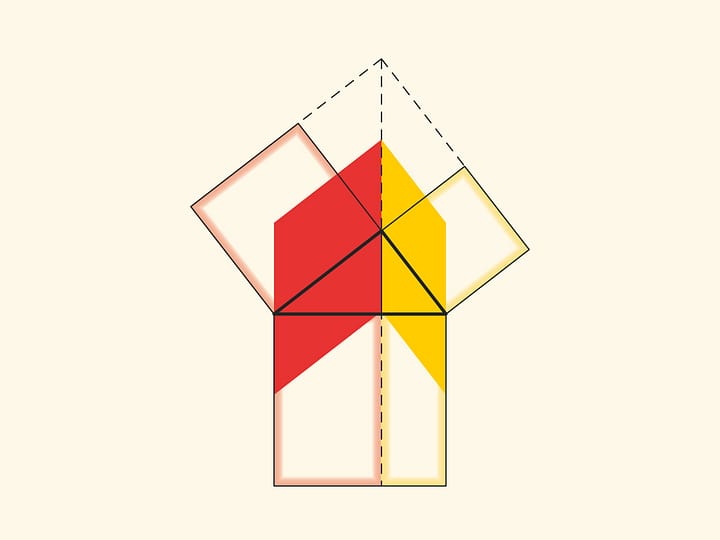

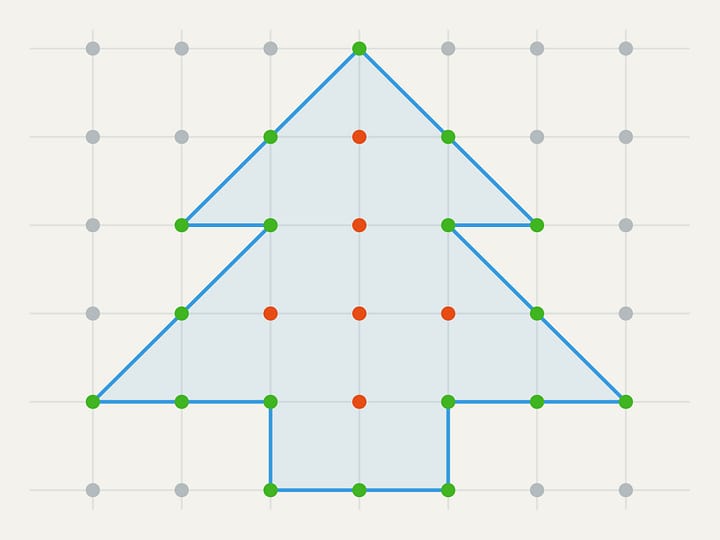

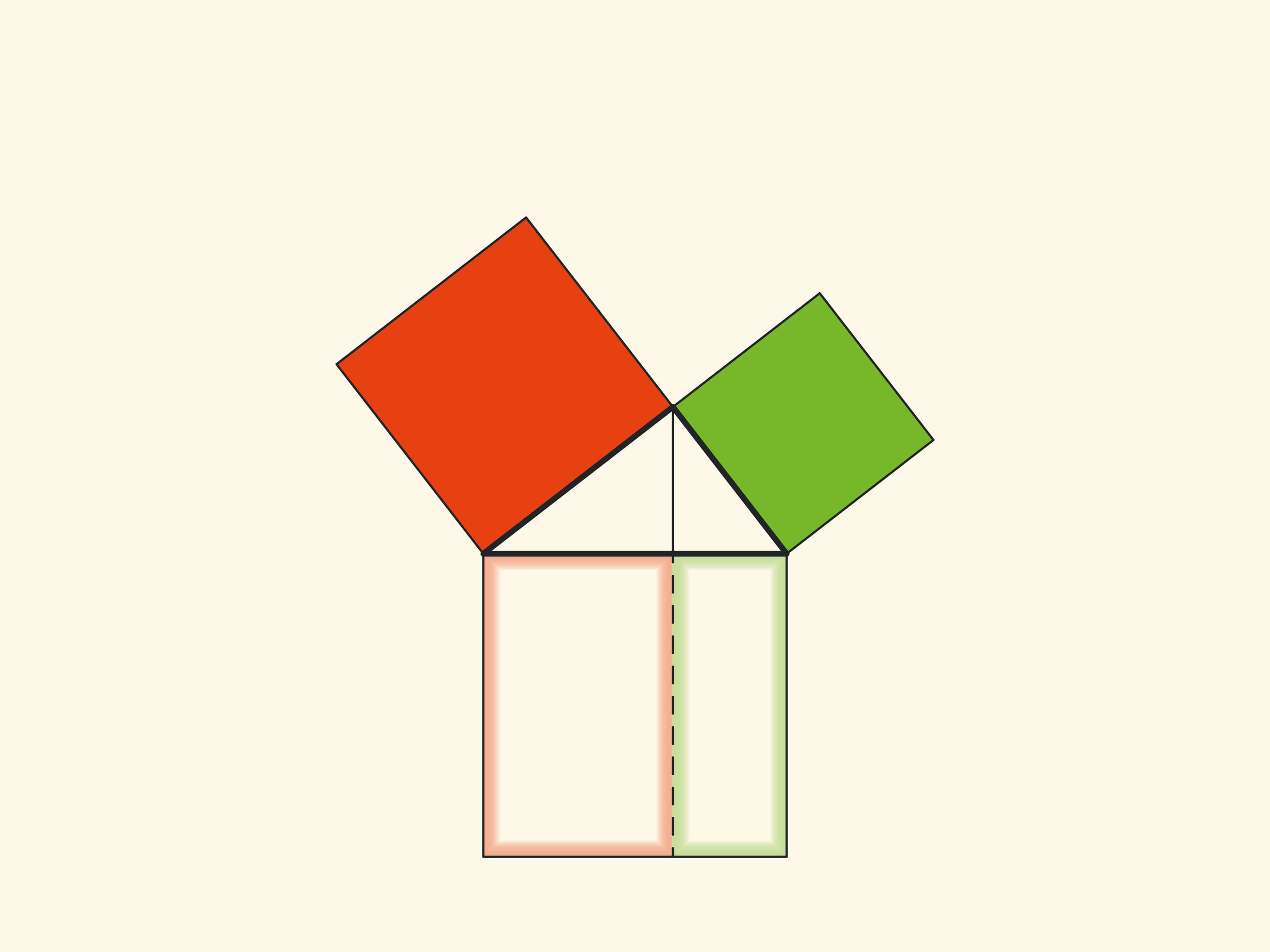

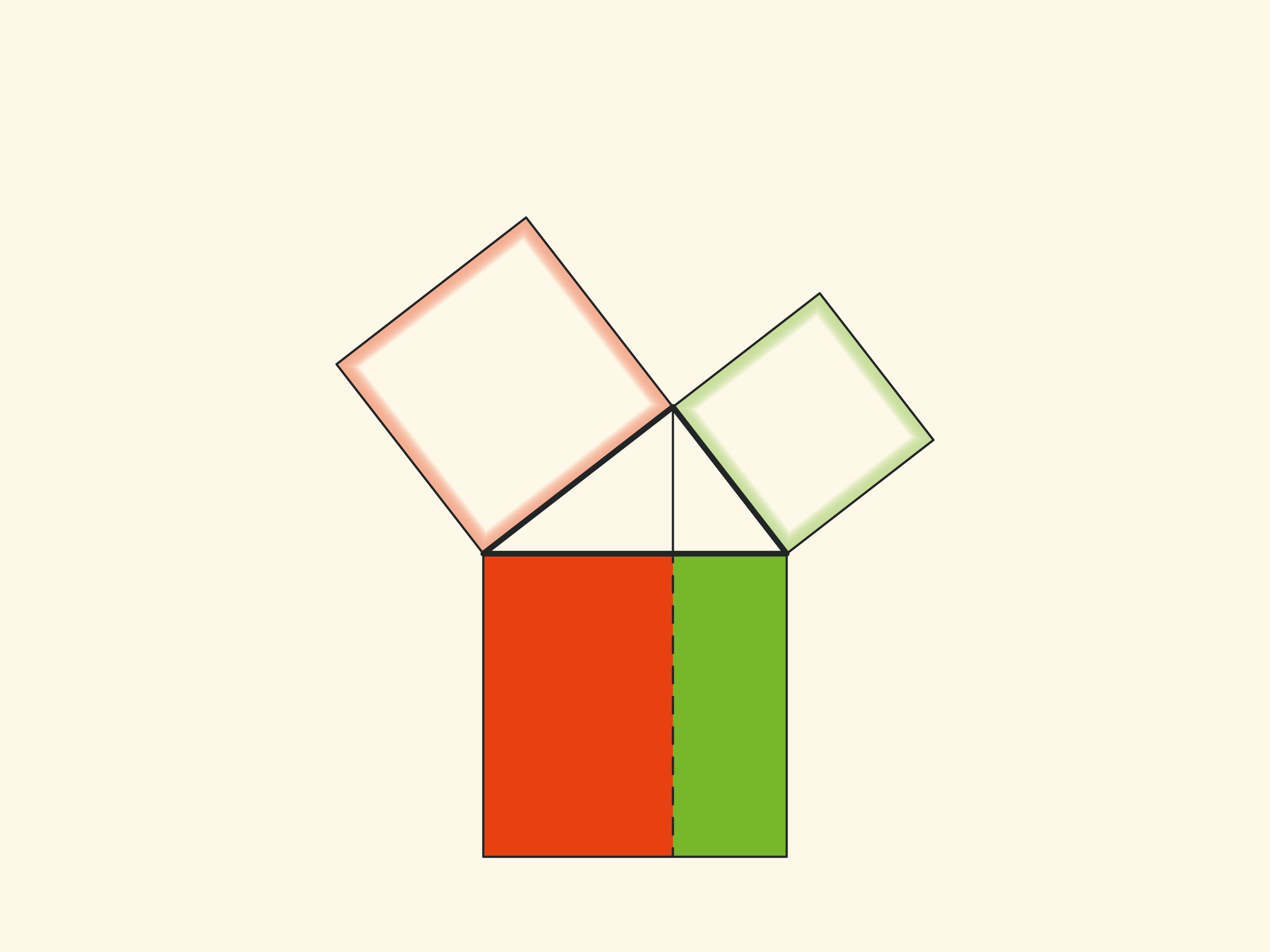

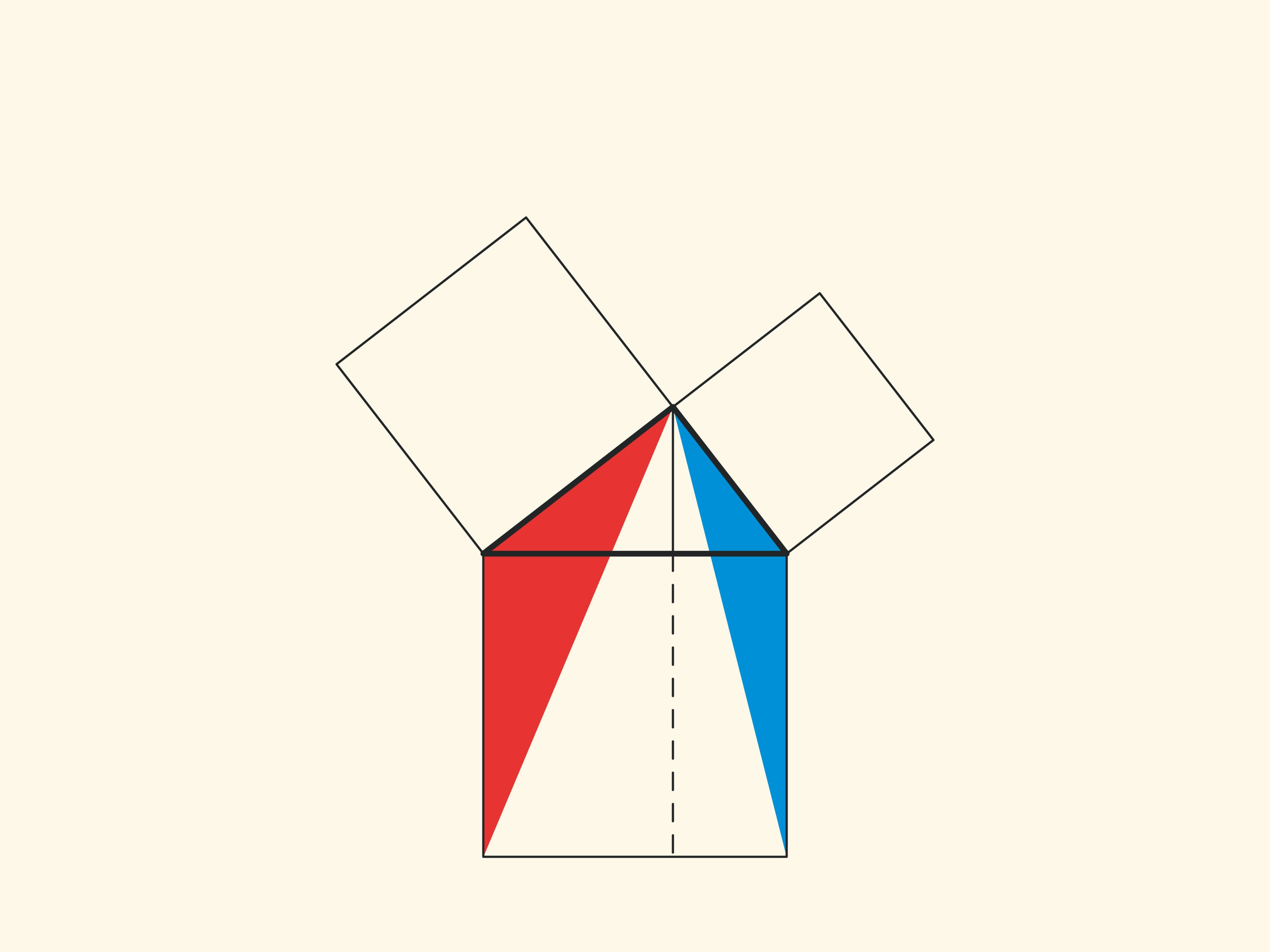

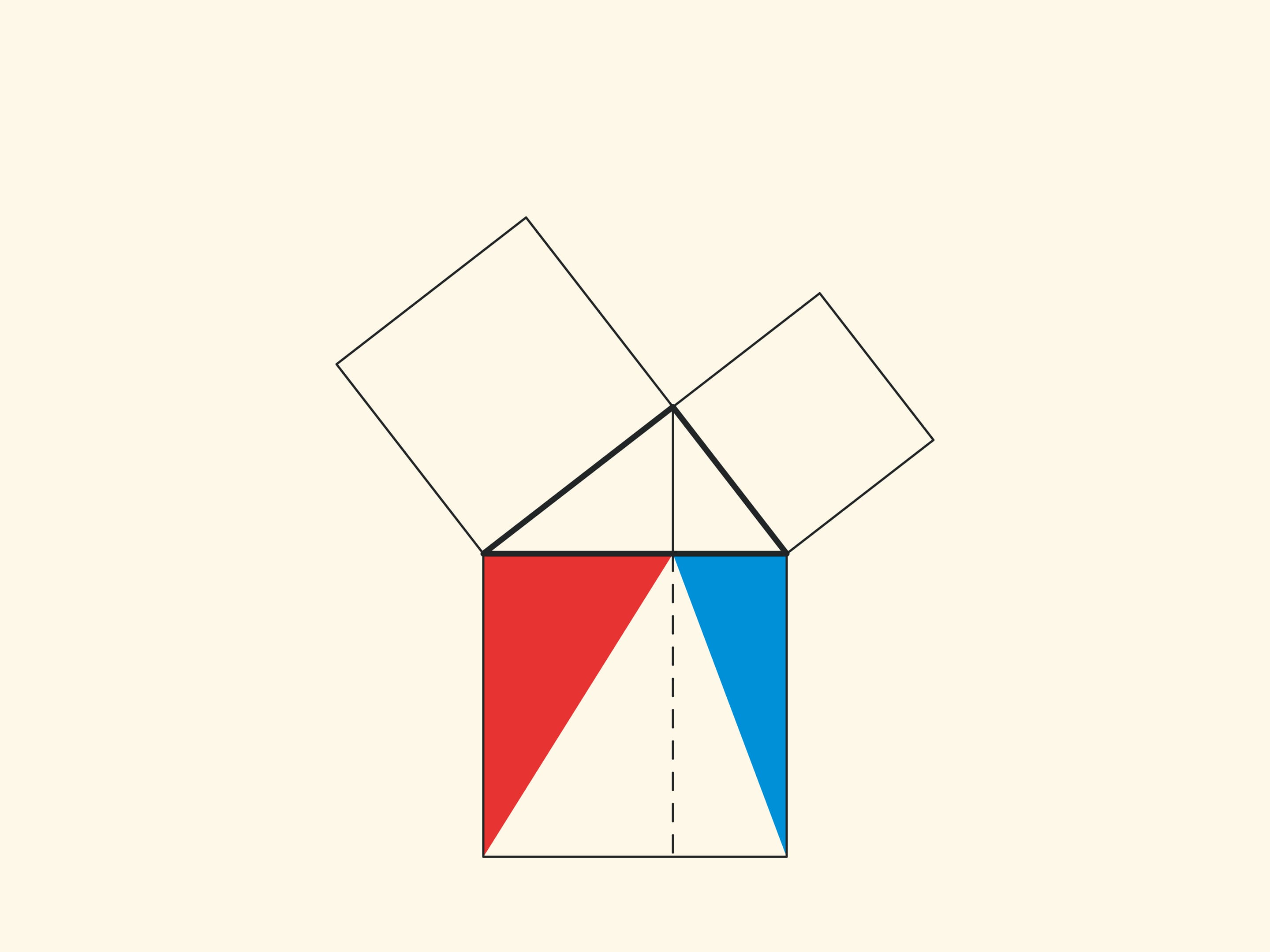

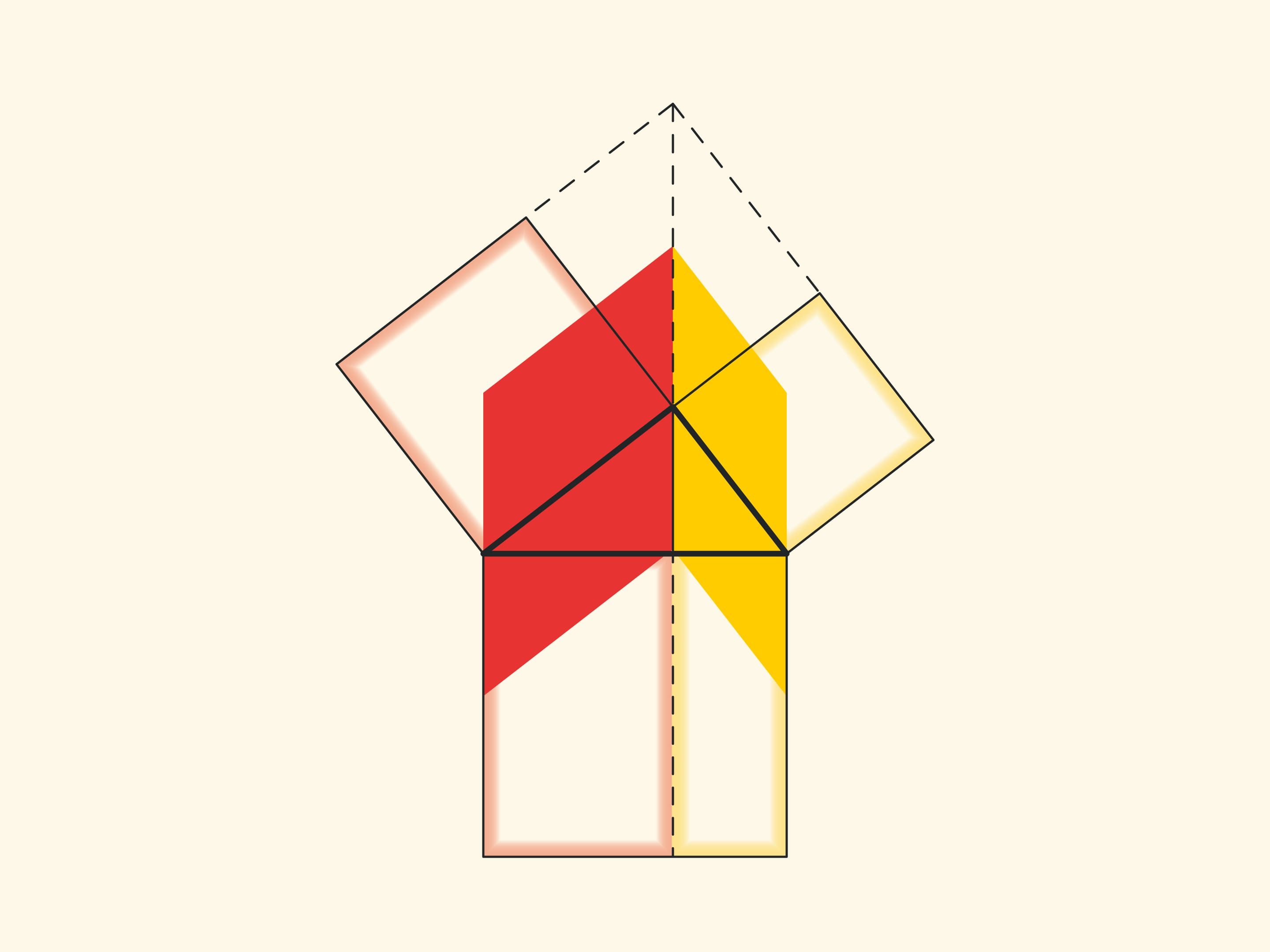

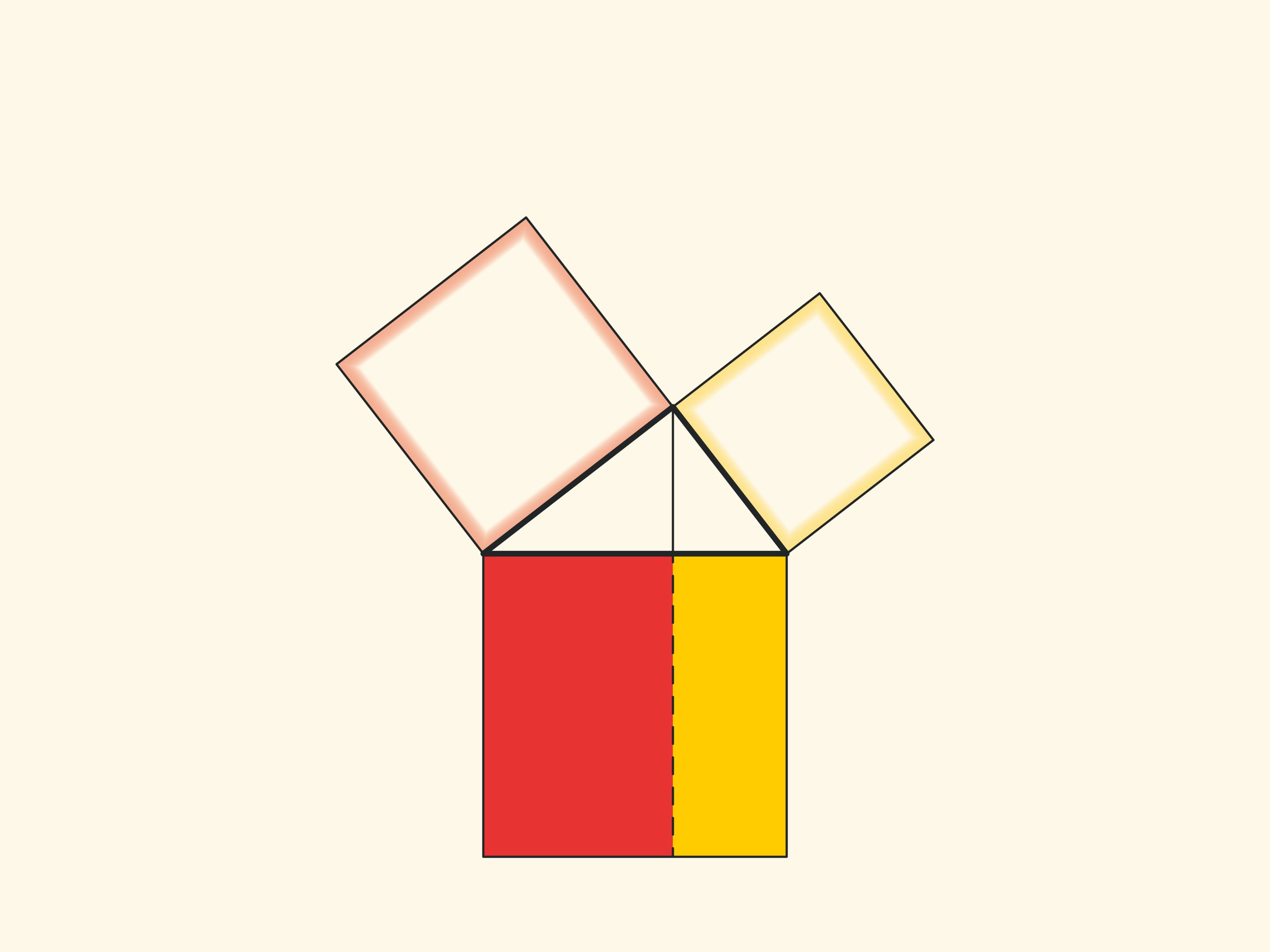

An elegant and elementary proof of the Pythagorean theorem of the type “Look!”, essentially analogous to that given in “Elements”, may be presented in pictures. Let us divide the square built on the hypotenuse into two parts by the continuation of the altitude of the right triangle dropped from the vertex of the right angle. It turns out that the smallest of the resulting rectangles is equal in area to the square built on the smaller cathetus, and the larger is equal to the square built on the larger cathetus.

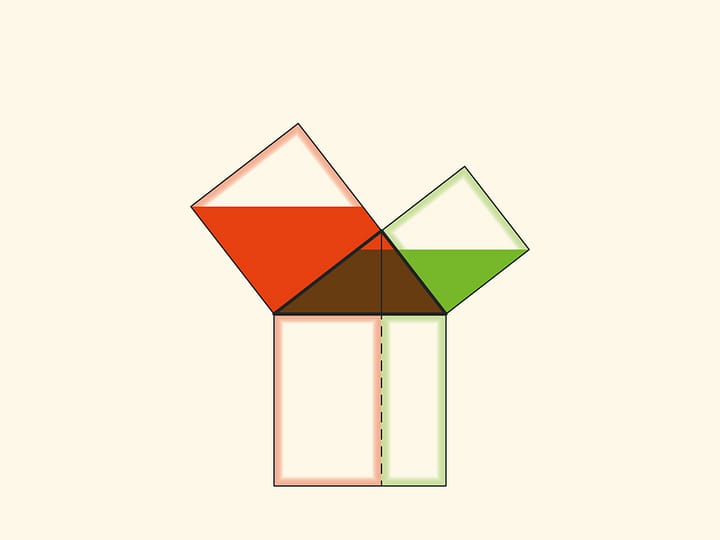

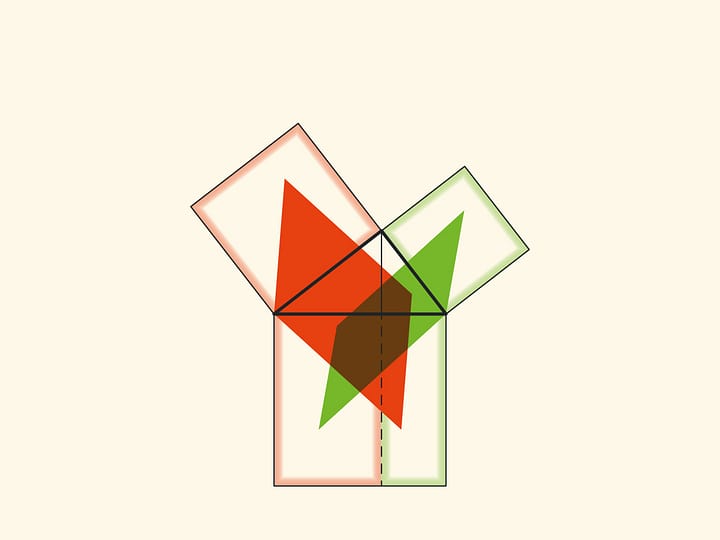

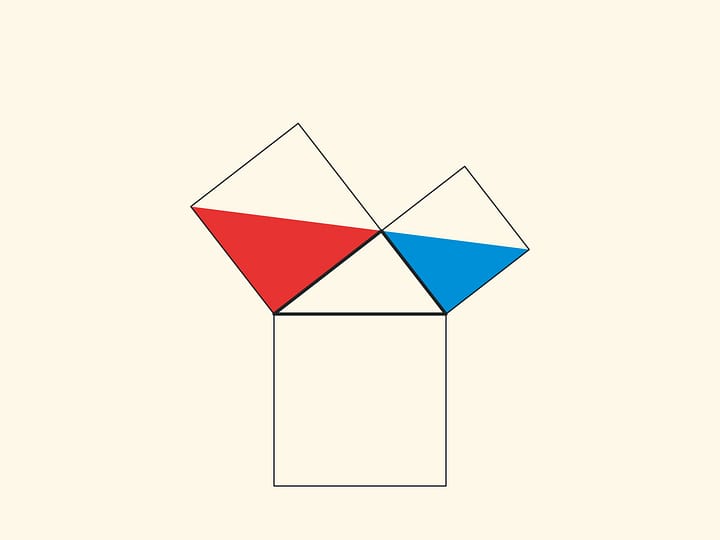

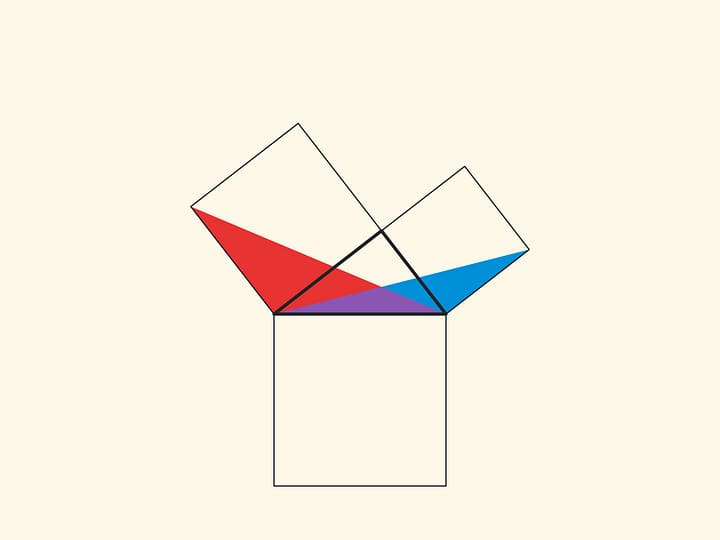

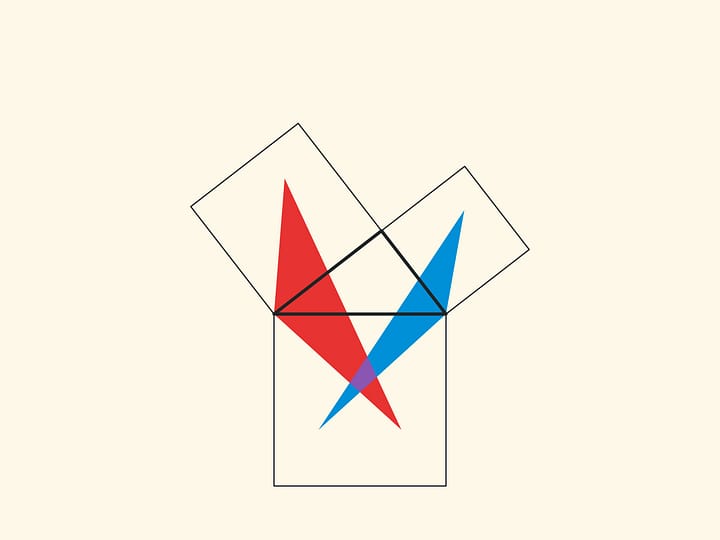

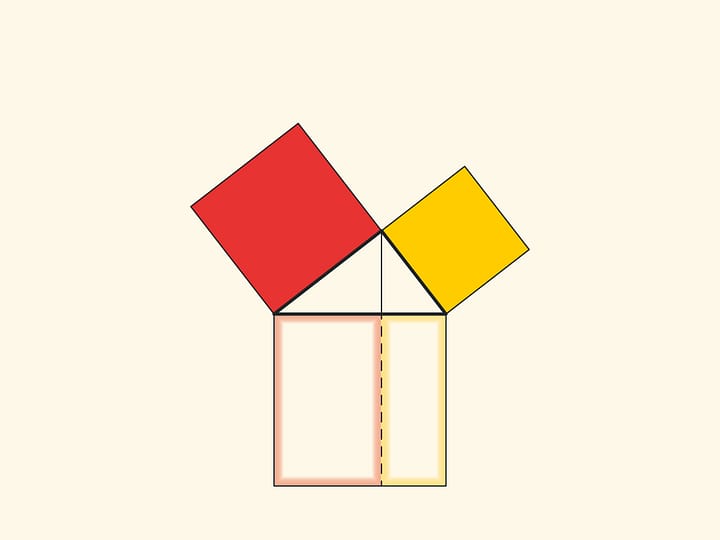

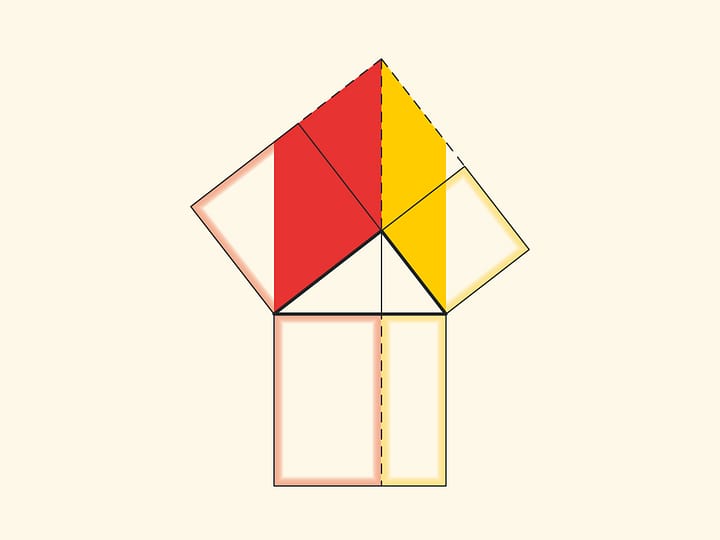

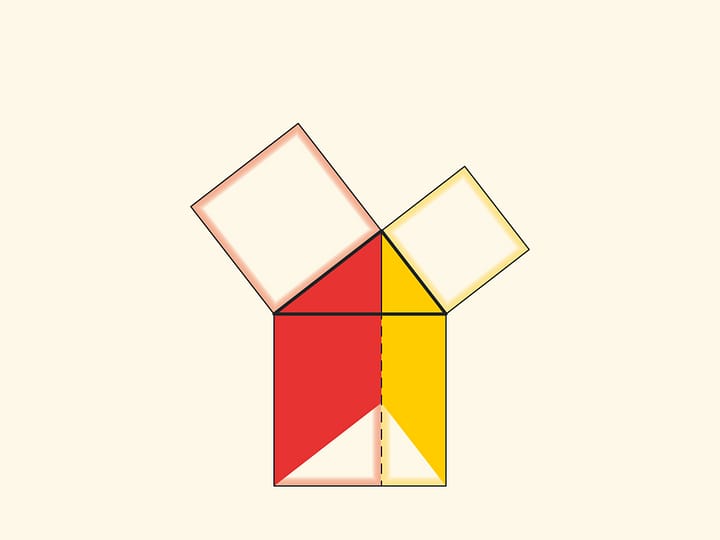

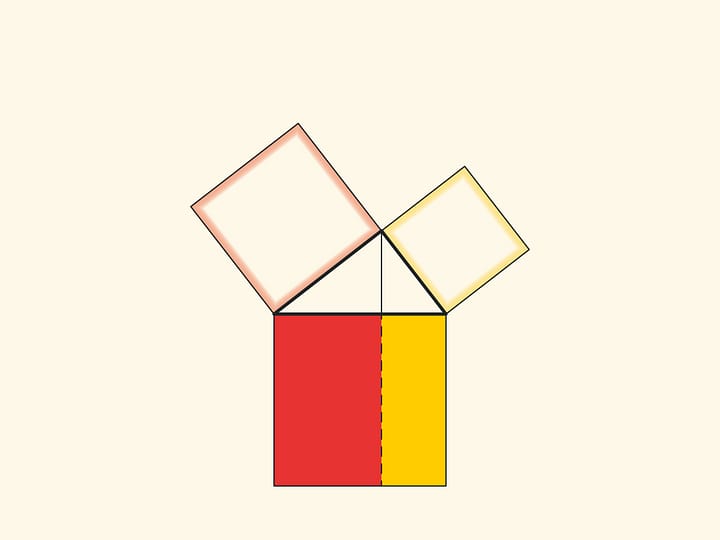

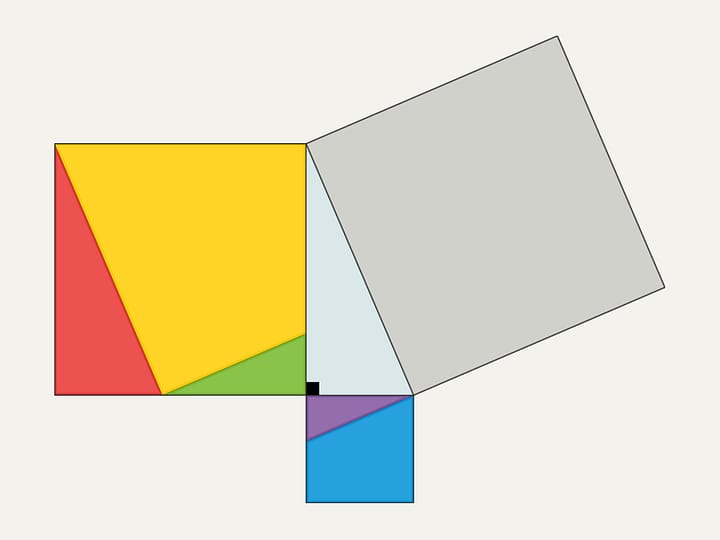

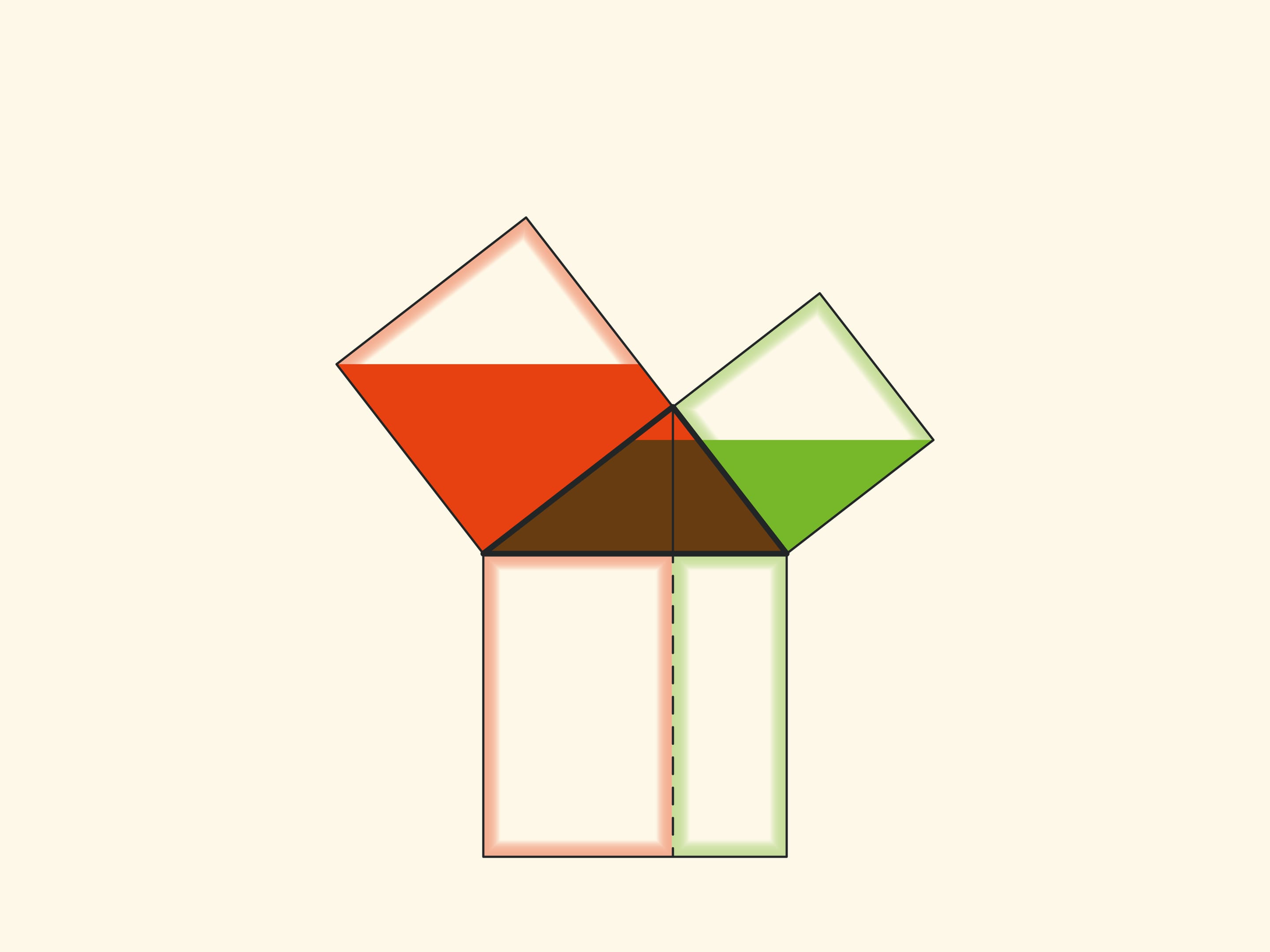

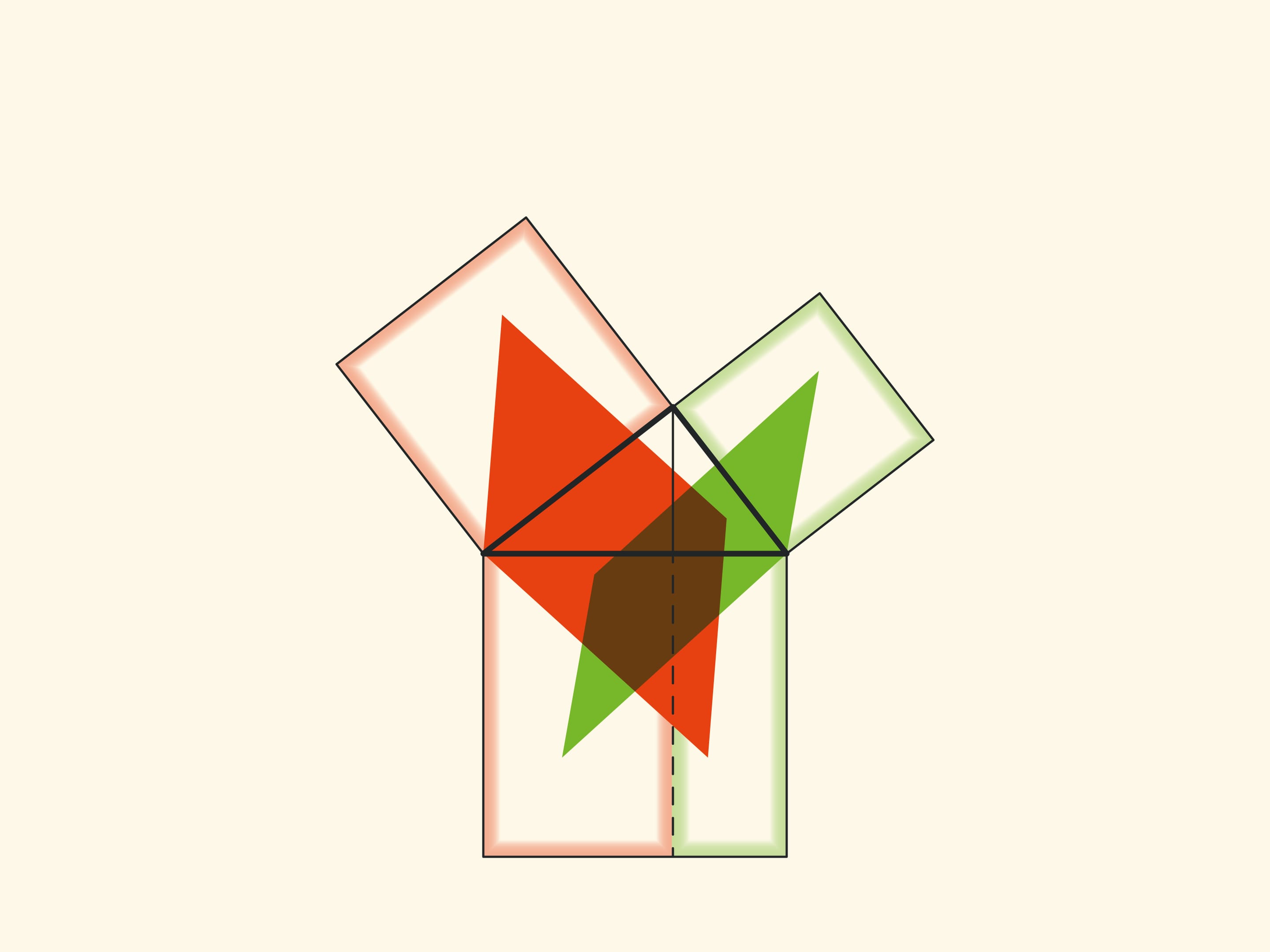

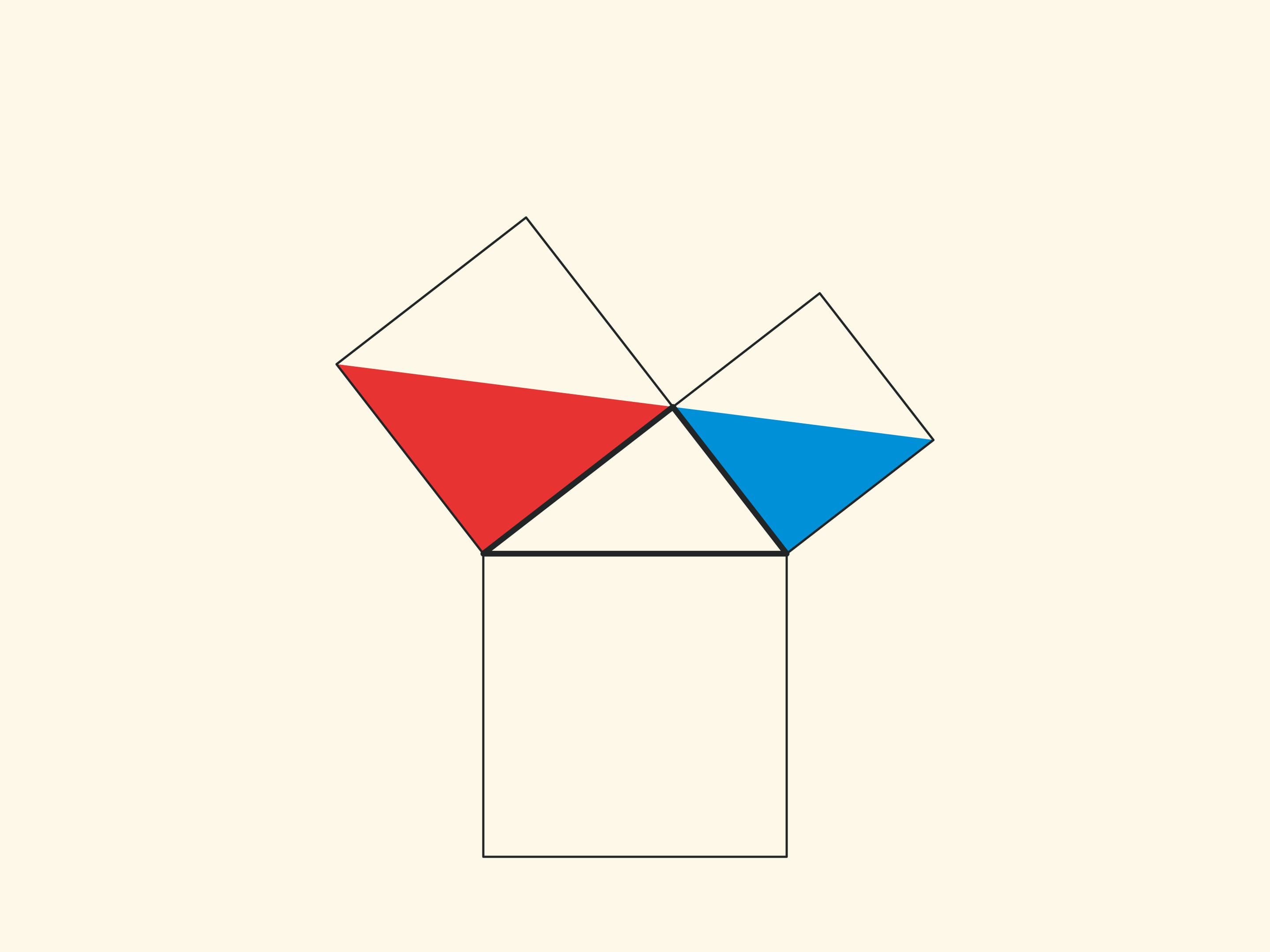

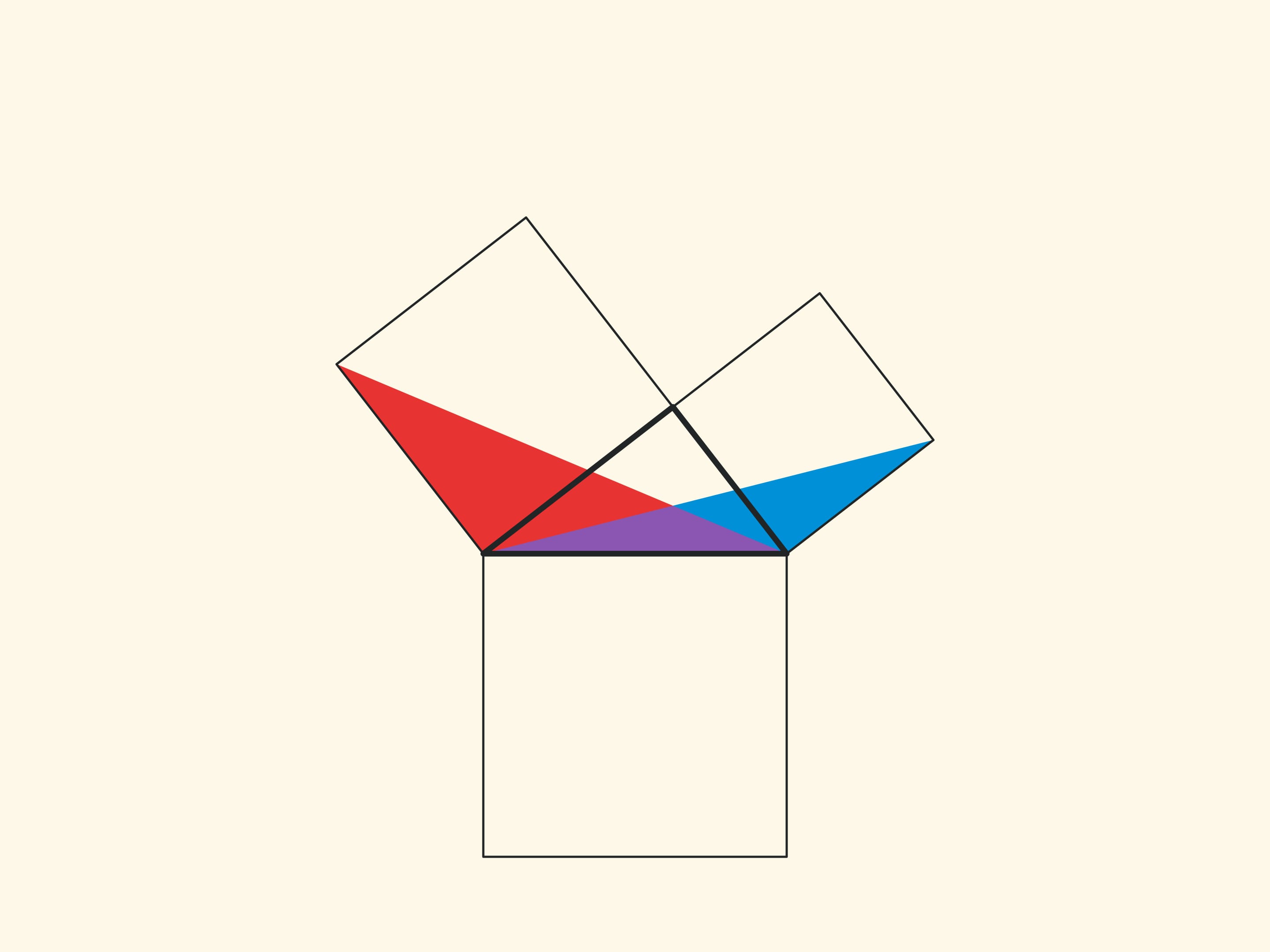

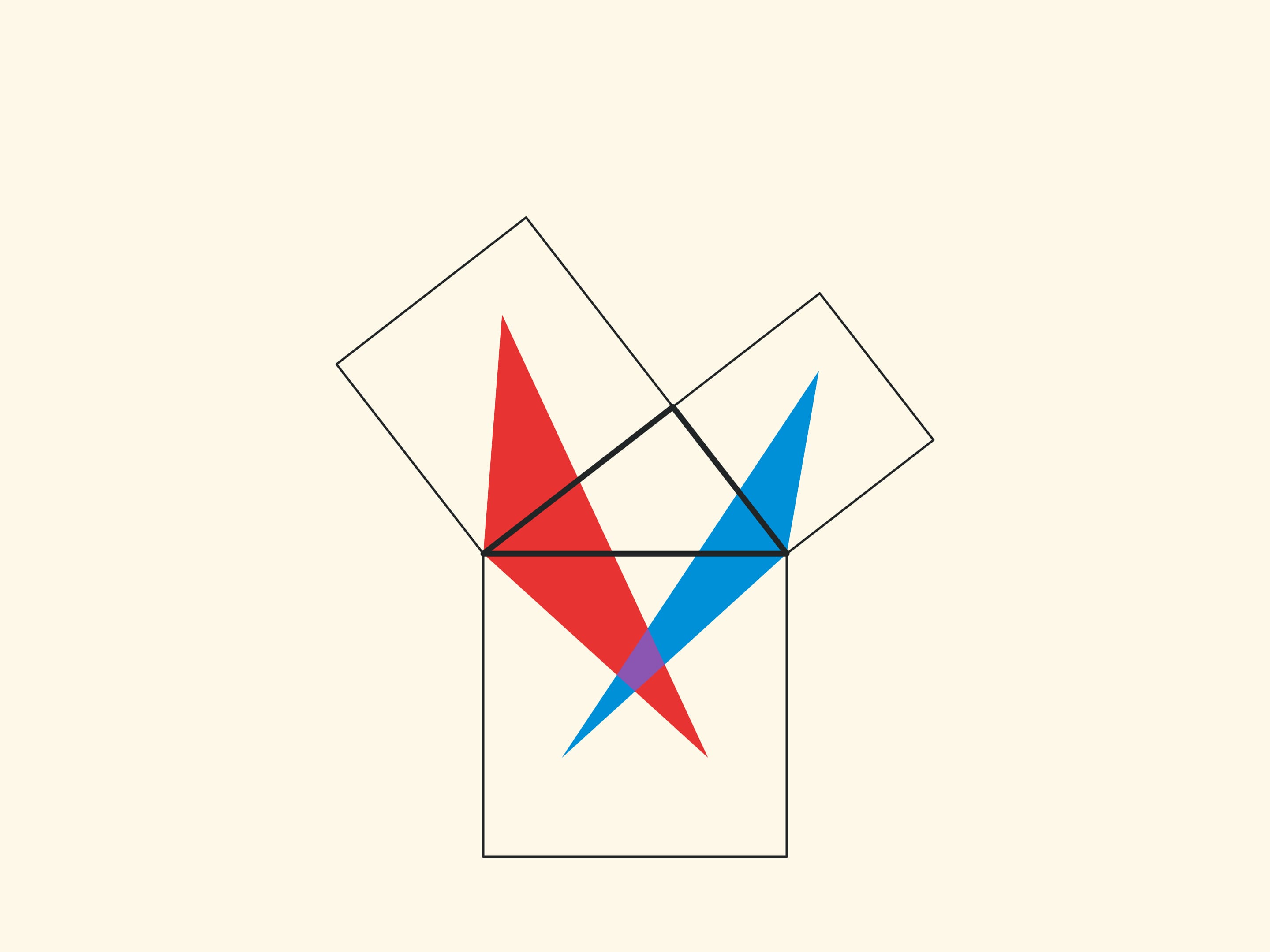

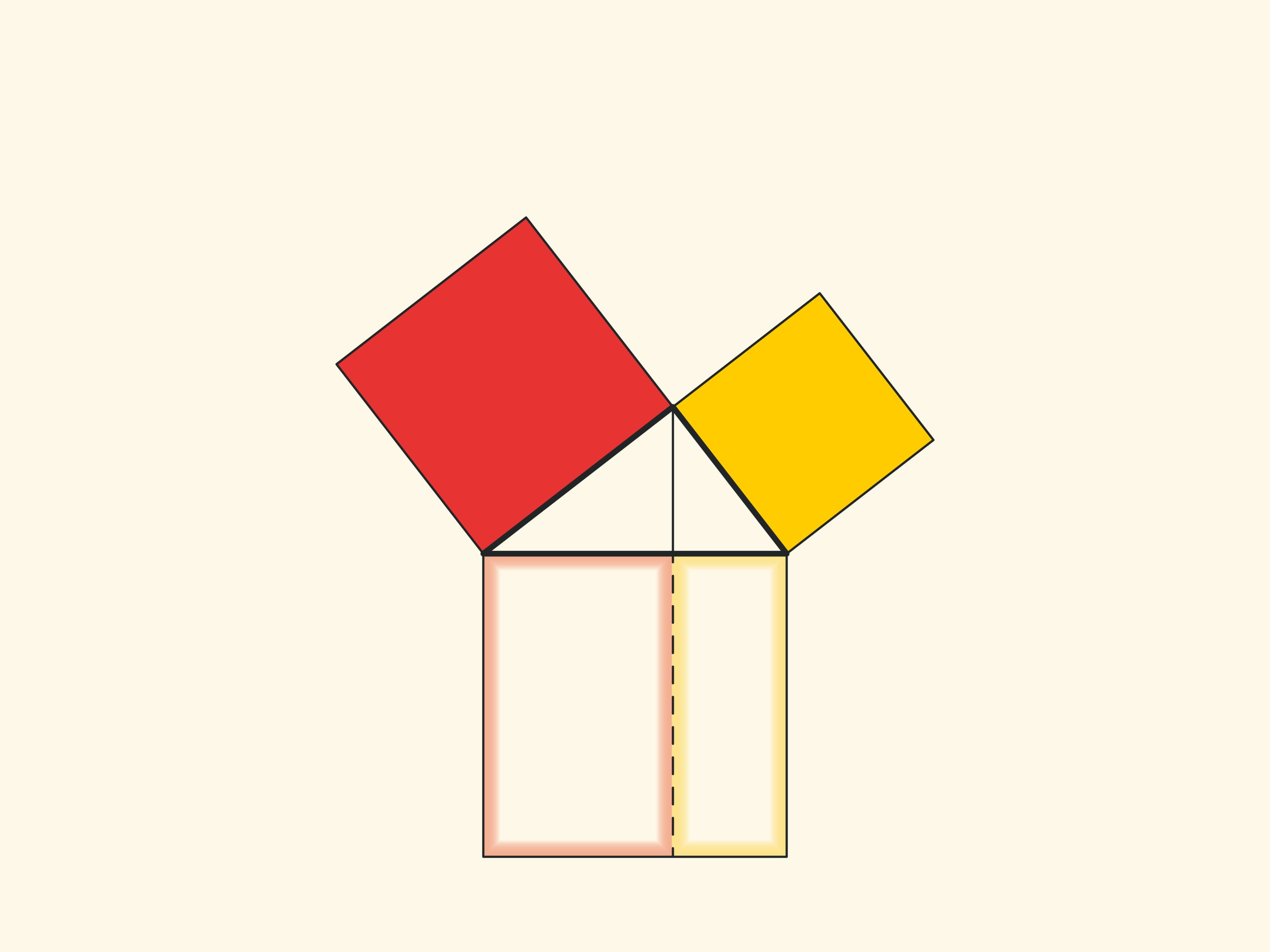

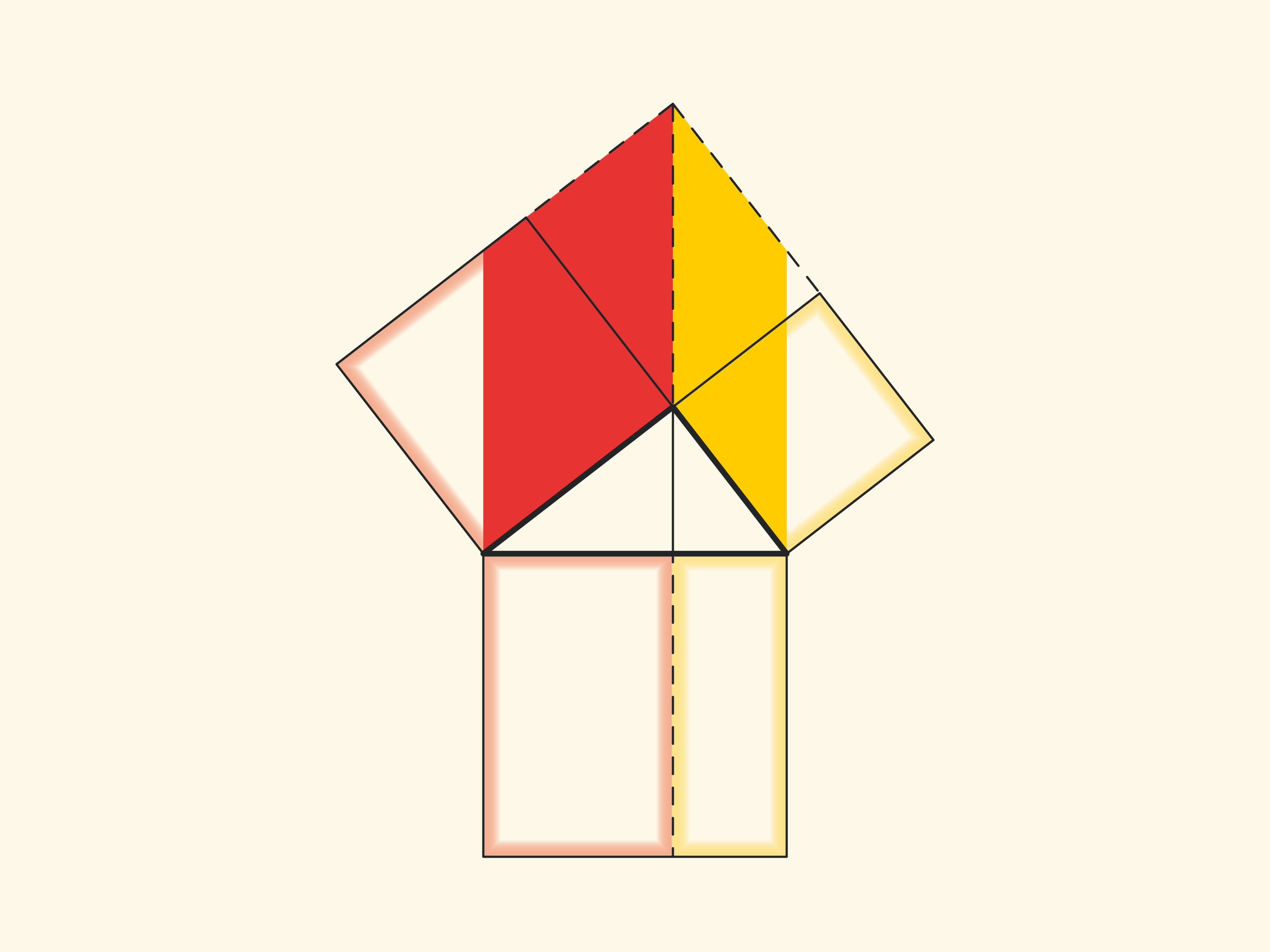

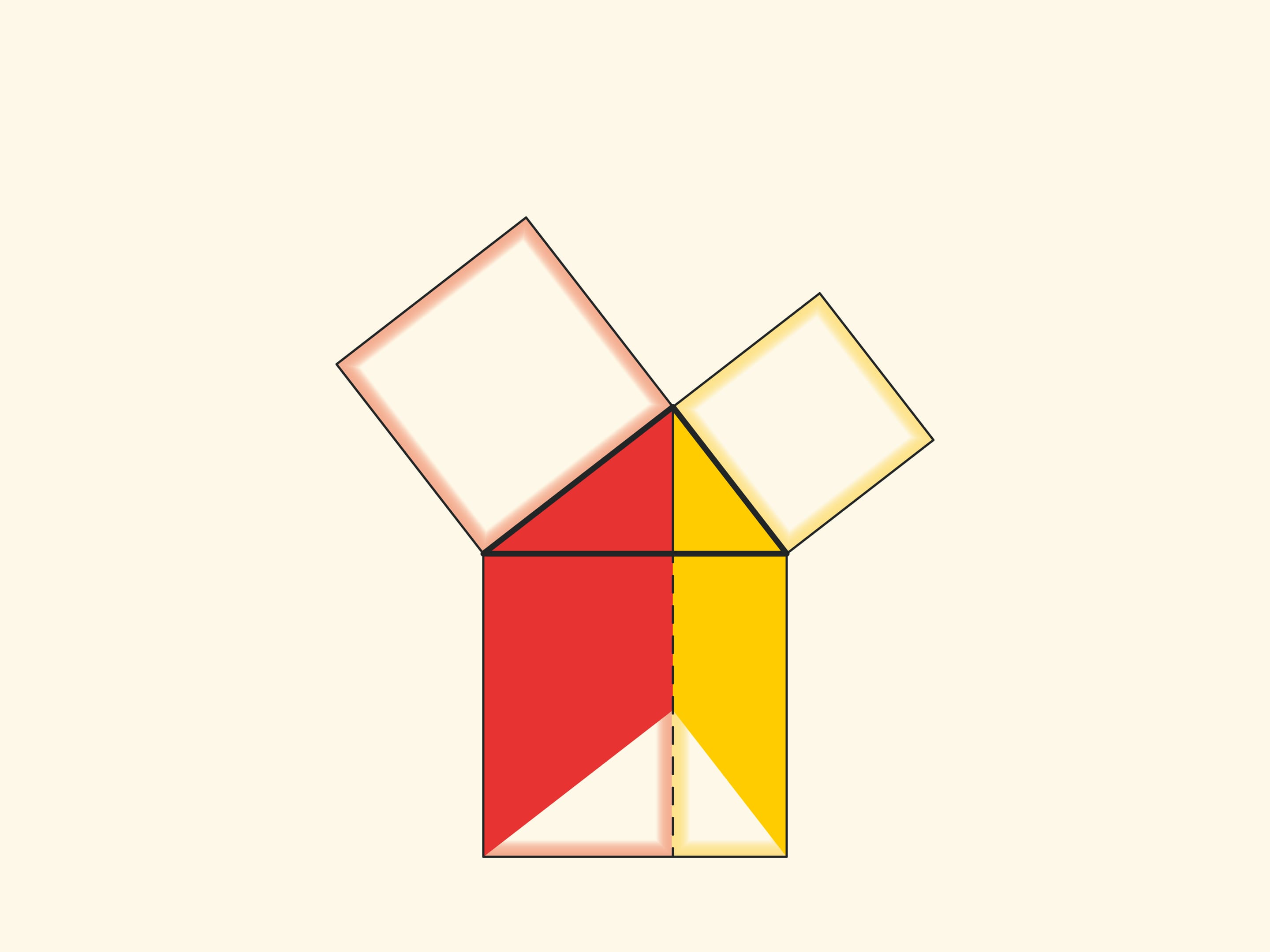

In the variations of Euclid’s proof below, the areas of the figures do not change when they are skewed: their bases and heights always remain constant.

When parallelograms are rotated with respect to the vertices of acute angles, their sides will lie on the height because their vertices will be at the vertex of the right angle. Indeed, the side of a small square is rotated 90 degrees and goes to the side of a triangle; and the long sides of parallelograms are parallel to the sides of the square on the hypotenuse. The difference from the proof given in “Elements” and called “windmill proof” is that Euclid did not use animation and considered not the parallelograms themselves, but the triangles which are their halves.

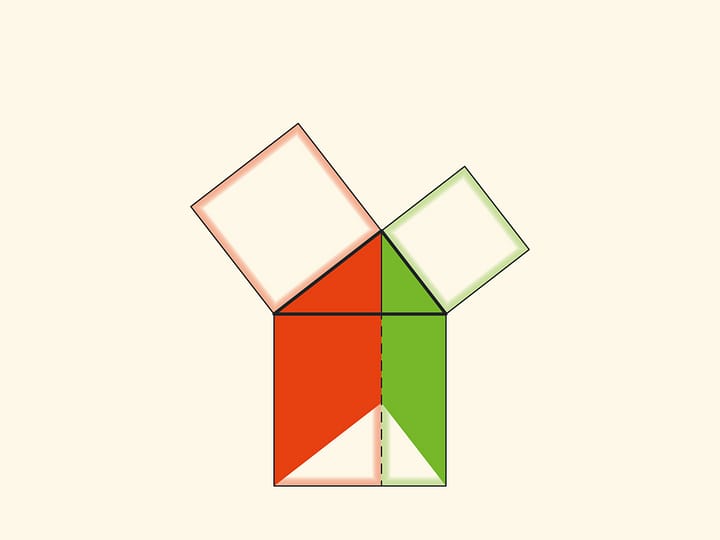

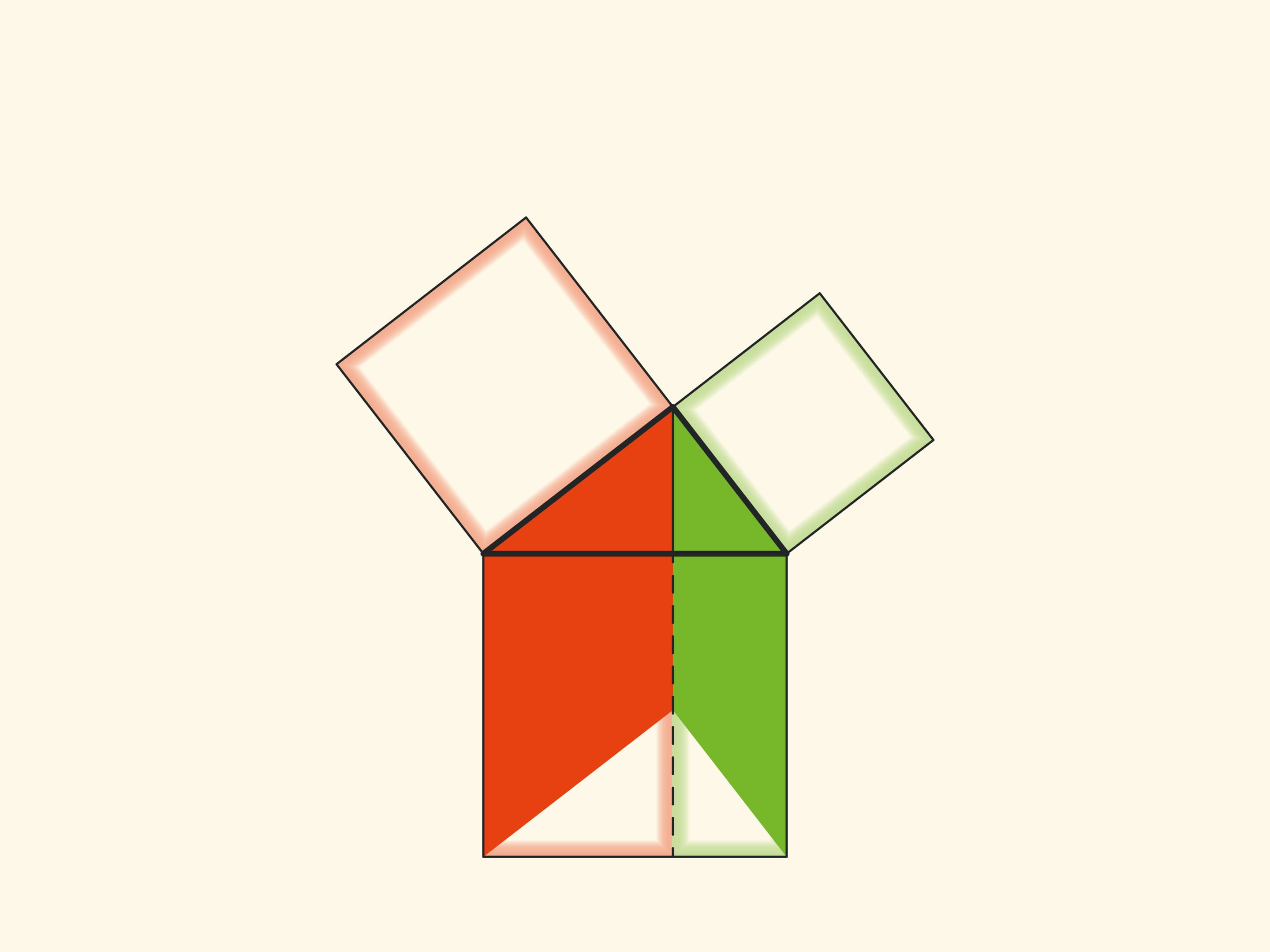

Another similar proof is to extend the sides of the small squares until they intersect.

With such a proof, one has to think about and justify why the point of intersection turns out to lie on the continuation of the altitude.